Interview with Harvard University Professor Andrew Gordon, second winner of the NIHU International Prize in Japanese Studies

“If I were given the chance to live my life again, I would like to be a historian again.” So says Professor Andrew Gordon of Harvard University, who has earned much acclaim for his research on modern Japanese history and wide-ranging educational endeavors spanning many years. Recently, Professor Gordon became the second winner of the National Institutes for the Humanities International Prize in Japanese Studies. In celebration of receiving the prize, we asked Professor Gordon what initially sparked his interest in Japan and his desire to become a researcher. We also asked him to offer a few words of advice for young people thinking of embarking on an academic career.

What was it that initially sparked your interest in Japan?

In the summer before my final year of high school, at the age of 17, I participated in a study program on Japan. It so happened that a social studies teacher at my public high school outside Boston (Mr. Altree) was the program leader that year. There were few spaces open in the program and he suggested that I might like to join. So I spent about 9 weeks taking part in the program. The first 10 days were spent at Mount Hermon School, a private senior high school in Massachusetts (now Northfield Mount Hermon School). We slept in a dormitory and studied Japanese language and history intensively. The other 8 weeks were spent in Japan, with long stays in Kyoto and Tokyo. We also took a quick tour of Hiroshima, Kyushu, and the Sanin and Tohoku regions before returning to the United States. Having grown up in the suburbs of Boston, I knew little or nothing about Japan, so I joined the program expecting an encounter with the exotic Orient. Yet, after visiting the country, I found a society that was surprisingly similar to the one in which I lived. And this surprise led to my continuing interest in Japan.

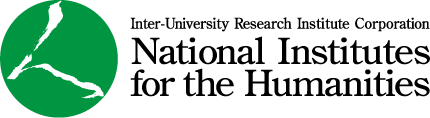

The study program to Japan included a homestay of about 4 weeks in Kyoto. This is Professor Gordon’s host family, the Nishiguchis. His friendship with the Nishiguchi family has continued for over 50 years. (Photo: August 1969, by Andrew Gordon)

It seems that what you experienced during the study program in Japan inspired some of your later research (modern history of Japanese labor). Among the many things you saw during the study trip what has stayed in your mind?

There are so many things. Just to mention a few, I remember seeing students from the Zengakuren (National Federation of Students’ Self-Government Associations) and Zenkyoto (All-Campus Joint Struggle Committee) in helmets and masks clashing with riot police in the west plaza of Shinjuku Station. A 4-week homestay in Kyoto was also memorable. In terms of what inspired my later research, the most significant experience was our visit to a Sony factory next to Shinagawa Station.

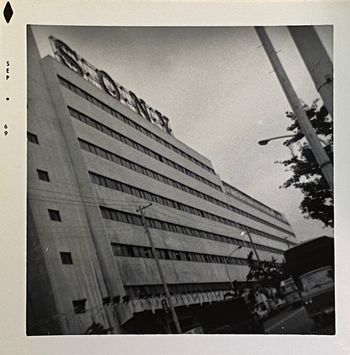

One of the most prominent features of Japan in 1969 was its booming economic growth. This was the time when radios, TVs, and many other “made in Japan” products were being exported all over the world. The Sony name was so famous that even American high school kids like me knew it. At the Sony factory, I recall looking down through the glass at the assembly lines. The women working on the lines had only junior high school-level education, but the company offered them financial assistance to complete their high school studies at night school while they worked in the factory during the daytime. On the other hand, we were told that men continued to work for the company until their retirement. This was my first encounter with Japan’s lifetime employment system mostly for men.

My intellectual curiosity was piqued, I guess. In the spring of my first year at university, for the final report for my Japanese Society class, I had wanted to write about Japan’s lifetime employment system, but when I told my professor, the late Ezra Vogel, who was an early career researcher at that time, he replied that the topic was too broad. I ended up writing my report on the rapid growth of the Soka Gakkai movement instead.

As part of the study trip to Japan, Professor Gordon and his study trip colleagues visited the Sony factory next to Shinagawa Station in Tokyo (Photo: July 1969, by Andrew Gordon)

What was it that attracted you to pursue an academic career?

It was a desire to satisfy my intellectual curiosity. The job of an academic is to identify a problem or a question, investigate it, and put together the discoveries in a book or article to let the world know about the findings. I found this process rewarding. I decided to become a scholar in the second or third year of university, but before that, I had also thought of becoming a journalist. The work of journalists and historians is similar because both investigate something and write about their findings. The difference is that journalists are given much less time than historians to research and write on a given topic. Another thing is that scholars have the responsibility to teach their students about their research findings, in the form of lessons. I felt that I would also enjoy teaching, so in the end I chose to pursue a career as an academic.

You must have visited Japan on numerous occasions over the years. Where are places you like most?

Oh, there are so many places. If I had to choose, I would say Tokyo and Kyoto. What I like most about Tokyo are the little shopping districts around each train station. Despite being such a large city, even the smallest stations—those where only local trains stop—all have a little shopping hub, almost without exception. This presence of little shopping streets is one of the things that makes Tokyo such an easy and appealing city to live in. In the case of Kyoto, the whole city is like a museum of living history. People have lived along the Kamo River since the Heian period. The fact that the scenery I see as I ride a bicycle along the river is much the same as what the people of Heian saw, is inspiring. Kyoto gives you the feeling that history is alive, which is why it is one of my favorite cities.

Ever since his homestay in Kyoto in 1969, Professor Gordon has remained good friends with the Nishiguchi family. Here he and his wife are pictured with the family of his “host sister” (the daughter of my “host parents”) at the Buddhist temple Jingo-ji.

What advice would you give to young people considering a career in academia?

In recent years, it has become very competitive to become an academic. Even if you graduate with outstanding results from a top-class university, securing a job is not easy. At the same time, it may take 6 or 7 years of solid research to obtain a doctorate. I would say that if you are thinking of becoming a scholar and studying history, ask yourself this: How would you feel if after 6 or 7 years of study, what you learn does not lead you to a job in academia? You might end up working as an analyst in the financial industry. Or you might feel the need to go back to law school and become a lawyer. Would you end up feeling regretful? If you felt that what you will learn is valuable and interesting in its own right, then I would say go ahead, by all means. This might seem like a harsh message, but I feel that it is important to keep these realistic possibilities in mind from an early stage.

A recent photo of Professor Gordon, taken at Nezu-jinja Shrine in Tokyo’s Bunkyo-ku (2020)

(Interview: Ayumi Koso)