Interview with Yasuaki Watanabe, new Director of the National Institute of Japanese Literature

In April 2021, the National Institute of Japanese Literature (NIJL) welcomed Yasuaki Watanabe as its new director. An author of many books, especially on classical Japanese poetry (waka), Watanabe is highly regarded for his easy-to-understand educational videos and teaching about Japanese language. To our surprise, he says he was shy as a child, and that he decided to pursue research because he found it hard to speak before people. When we asked Professor Watanabe about his motivation for studying the history of waka, he says it comes from the urge to express himself through his own words and to learn the secrets of writers.

(1) How did you first become interested in waka?

As a boy, I found it difficult to speak in front of others. There were many things I wanted to say, but I could not get the words out of my mouth. I would feel as if my head would burst. Then again, being an avid reader, when I did speak, I would talk oddly like a grown-up—that is, if I managed to converse at all—and that startled people, making matters even worse. When I started junior high school, I began trying various new things in hopes of changing myself.

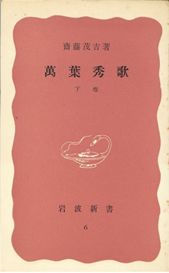

Two memorable things happened in eighth grade. First, I read prominent Japanese poet Saitō Mokichi’s (1882−1953) Man’yō shūka [Fine Verses from the Man’yōshū] (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1948). My studious father gave me the book, telling me to read it before a family trip—which he planned at the time—to the Japan World Exposition 1970 in Osaka and the locations featured in the eighth century Man’yōshū [Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves] poem collection. Despite containing many errors, the book is a unique work that reflects the author’s fascination with and passion for the Man’yōshū. I was deeply impressed by the book, and my excitement doubled as I saw firsthand the sites that inspired the poems. I still remember how my teacher complimented me when, sometime later, I handed in some photos that I took, accompanied by a report on the Man’yōshū.

The second memorable event was my coming across tanka poems by poet, dramatist, photographer, writer and film director Terayama Shūji (1935−1983). I recall a young Japanese-language teacher at my cram school showing me a mimeographed sheet; on it were the multitalented artist’s sonorous verses—Matchi suru / tsuka no ma umi ni / kiri fukashi / mi sutsuru hodo no / sokoku wa ariya [lit., Lighting a match / for a brief moment I see / the misty ocean / is there a motherland / worth offering my life for] was one of them—and they strongly resonated with me. Reading Terayama’s poems, I came to think that expressing myself through such a format might allow a shy person like me to better interact with others on an emotional level.

Man’yō shūka [Fine Verses from the Man’yōshū] (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1948). Professor Watanabe received this two-volume book from his father. “My father’s parents had died when he was young, and after he grew up he became the manager of a small factory. But he was a studious man, reading books late into the night. He was extremely knowledgeable on topics ranging from literature to the state of society—and was exceedingly interesting to talk to.”

(2) We heard that as a student, you became absorbed in theater with famed playwright and director Noda Hideki (b. 1955). You were an actor but decided to become a scholar? What inspired you to change course?

I trace my interest in theater back to junior high, but the turning point was my first year in high school. I saw a play performed by older drama club members of the school, and became spellbound: As the play starts the characters rush downstage saying such “ism” words as “Bolshevism” and “Stalinism,” and then we hear the protagonist say, “Who are you trying to impress?”

In the middle and late 1960s, theater was a medium through which young people expressed their ideology and ideas; theater clubs were dens of activists in the student often-radical movement, then revolving around opposition to the Japan-US security treaty. Those of my less-vociferous generation, which came a little after the activism peaked, were disparaged for our apathy, indifference, and irresponsibility. Combined with the difficulty I had expressing myself, the culture of my generation then was a source of great frustration. After seeing that play put on by the upper-class students at high school, my mindset changed entirely; I realized that people didn’t have to have an ideology to express themselves. The student playing the lead role of that performance happened to be Noda Hideki, with whom I later started the theater company Yume no Yūminsha.

I had devoted myself to theater as a university student, but four years or so after forming the company, I started to feel I had hit a wall. I increasingly struggled to remake myself as an actor, whereas my interest in scholarship was getting stronger. The urge to express myself in my own words was growing, and I chose waka as the theme for my undergraduate thesis.

As a university student, Professor Watanabe was engrossed in theater. He read many philosophical books—including those on the body theory that was starting to gain popularity back then—because, he says, he wanted to “be cool.” All that reading later benefited him in his research on waka.

(3) The consistent theme of your research is why the waka tradition managed to continue for over 1,300 years. What draws you to this topic?

I started my research with waka—which has an established style—taking inspiration from Terayama Shūji’s following words: Nawame nashi ni wa jiyū no onkei wa wakarigatai yо̄ni, teikei to iu kase ga boku ni gengo no jiyū o motarashita. (“Boku no nōto [My Notes].” In Sora ni wa hon [The Book in the Sky]. Tokyo: Matoba Shobō, 1958; “Just as one cannot appreciate the blessings of liberty if one has never been bound, without fixed forms, I might not have grasped the freedom of language.”)

I realized that established forms both restrict and allow for artistic expression, and understanding this enables readers to better understand the intent of the artist. This was, for me, the fascinating discovery that eventually helped me define my research theme, which compares classical Japanese poetry to performance. This is demonstrated in Higi to shite no waka: Kōi to ba [Classical Japanese Poetry as a Secret Ritual: Action and Space] (Tokyo: Yūseidō Shuppan, 1995)—which I edited—and my book Waka to wa nani ka [What Is Classical Japanese Poetry?] (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2009). Getting to that point in my research, however, was full of difficulties. The turning point came with an essay I wrote in my mid-thirties, titled “Furumaeru’ sugata o megutte: Shunzei karon to setsuwa no setten” [Exploring the Term “Furumaeru”: The Connection Between the Poetic Treatises of Fujiwara no Shunzei and Setsuwa Narratives], first published in the journal Kokugo to kokubungaku [Japanese and Japanese Literature] in January 1993 and later included in my book Chūsei waka no seisei [The Development of Medieval Period Waka] (Tokyo: Wakakusa Shobō, 1999). The essay discusses my idea that behind the term furumau—a word used in the context of waka critique—lies the world of setsuwa that centers on physicality. Confident that my argument was compelling, I submitted the essay to the refereed journal and, thankfully, the comments were favorable. Based on that article, I went on to shape my theory about the dramatic elements of waka.

(4) You have written many books for students in junior and senior high school and university. From your teaching career up to now, please share with us classroom experiences that were memorable for you.

Two come to mind. One is a theater class I taught at Komazawa University as a part-time teacher; the other was a demonstration class in classical Japanese I taught at the University of Tokyo. I designed the former at the request of a senior member of the university department I belonged to, who asked me to create an introductory class on theater for his students. Unable to come up with any idea, I wrote to an old friend from my Yume no Yūminsha days. My initial plan was to have a guest speaker for a couple of classes, but I ended up conducting a drama workshop under my friend’s guidance. The workshop consisted of four steps—each participant calling one another by their first names; making eye contact; making physical contact; and moving in sync—after which the students developed a play. I later incorporated this activity into “Experiments in Teaching the Japanese Classics,” a demonstration course for student teachers that I gave at the University of Tokyo. I set it up to offer participants an opportunity to play the parts of both instructor and student, but the workshop resulted in intense interaction among the class members. In a demo lesson on writer and poet Akutagawa Ryūnosuke’s (1892−1927) novel Yabu no naka [In a Grove] and the Konjaku monogatari shū [Tales of Times Now Past] upon which the writer’s story is based, the candid and forthright opinions from the students sometimes made it difficult for me to keep the class on track. The workshop proved to be an enlightening and insightful experience for me.

Professor Watanabe’s workshop theater class became a popular course at Komazawa University and went on for a decade. Students cleared the desks and chairs of their classroom and moved their bodies to engage in a theatrical performance.

(5) Please share with us what you hope to accomplish as new NIJL Director.

NIJL is promoting the “Model Building in Humanities through Data-driven Problem-solving” Project, an undertaking in which I, too, am involved. The digital technology used in the project is amazing, while it makes me think that going further, we would need to explain to people what significance there is in digitizing classical Japanese texts. Both Japanese literature and NIJL have limitless possibilities; what, then, are the aspects that algorithms cannot capture, and how can we utilize digital tech? We hope to exceed all expectations on these topics while reinforcing the organization of NIJL. Classical texts are full of life lessons that people can learn from, which is all the more reason for us human beings to determine how to relate to technology—and, furthermore, be in control of our relationship with the digital world.

(Interviewer: Shiori Kume, Liberal Arts Communicator, Specially Appointed Assistant Professor, National Institute of Japanese Literature)

Yasuaki Watanabe, Director of the National Institute of Japanese Literature

Watanabe specializes in the history of classical Japanese poetry (waka). After graduating from the University of Tokyo Faculty of Letters, Department of Japanese Literature, he entered the Graduate School of the University of Tokyo. In 1986, he became an assistant in the University of Tokyo Faculty of Letters. In 1988 he became lecturer in the Faculty of Letters, Ferris University, and in 1993 assistant professor in the Sophia University Faculty of Humanities. In 1999 he became assistant professor in the University of Tokyo Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology and in 2006 served as professor there until assuming his current position in April 2021.