Interview with Liberal Arts Communicator Yuka Oishi

The National Institutes for the Humanities (NIHU) has been conducting research on human cultures from diverse angles to understand how individuals as well as nature and humans can harmoniously coexist with each other. To that end, we believe it is critical to facilitate communication between the researchers at the forefront of research and society.

As part of this effort to enhance such communication, NIHU holds various events for the general public and also provides training programs for liberal arts communicators who facilitate and engage in “two-way communication” between experts and non-experts. Who are these “liberal arts communicators?” What kinds of activities do they engage in? We will answer those questions in a series of articles.

The sixth article in this series is about Dr. Yuka Oishi at the National Museum of Ethnology (Minpaku). Dr. Oishi took her position as a liberal arts communicator from October 2018. We asked Dr. Oishi to look back on her projects as a liberal arts communicator and give us some tips on how researchers may embark on outreach activities.

You are a cultural anthropologist specializing in Siberia, as well as a liberal arts communicator. What are your research interests?

I am interested in the relationship between nature and human beings. I like cold regions, and I go on research visits to Western Siberia to explore the subsistence, such as, reindeer herding, fishing, hunting and gathering of the indigenous peoples in the area.

Of your activities as a liberal arts communicator so far, can you tell us about an experience that has been memorable?

I’m afraid most of my memorable experiences as a liberal communicator are not rosy. There has been a lot to learn. Each time I took part there were things that went wrong and I felt I could have done better. I have been involved in workshops for the general public and giving lectures at the National Museum of Ethnology. The event about which I have the most regrets was a workshop titled “Dare no bōshi? Donna bōshi?” (“Whose Hat? What Kind of Hat?”), held in the summer of 2019 at Minpaku (photograph 1). After I gave a brief lecture on hats, the participants closely examined head coverings borrowed from Minpaku researchers and each created head coverings of their preference, using materials such as paper and nonwoven fabric. The questionnaire handed in by the participants showed most of them enjoyed the event, so the workshop itself was not a failure.

Photograph 1: Scene from the workshop “Whose Hat? What Kind of Hat?” (August 2019, at the National Museum of Ethnology)

The problem may be the balance between specialized content and how it can be made interesting to the public. At Minpaku I have been a member of a working group that develops Minpaku’s social outreach projects. We are a group of four; two staff members of the Information Planning Section and two researchers, myself included. Part of our task is to develop workshops held outside Minpaku. One such outreach workshop was the hat-making event and we did a trial run at Minpaku (photograph 2).

In planning this event, we first examined the reports of workshops held previously at Minpaku. From among them, we chose a hat-making workshop, which had been very well received, and decided to develop a workshop based on it. We asked Minpaku scholars to provide us with head coverings that are worn in the regions they study, explanations about them, and photographs showing how they were actually worn. We then created a simple, portable exhibition kit for the workshop. We made trial head coverings and studied what materials would be needed. We also examined the headgear artifacts on display at Minpaku so that we could take the workshop participants on a tour inside the museum.

I was responsible for the opening lecture at the workshop. The lecture turned out to be hard to understand and the reason why I have the most regrets. When we opened the registration for the event, we did not place any limits on age for participation. The participants who gathered ended up varying in age from about three years to elders. The majority were elementary school children. In the lecture I talked about the diversity of head covering materials and shapes, as well as functions, symbolism, and decorativeness. I had tried to make the lecture as simple and easy-to-understand as possible so that children, the main participants, would understand. I had thought I had made it sufficiently concise, avoiding packing too much information into it. But the participants did not think so. Some pointed out that the lecture was difficult and too long for children participants.

I had similar regrets over and over after being involved in other workshops and study tours for college students. To convey how fun and interesting it is to study cultural anthropology, it is necessary to provide detailed information and unique points of view. I also think the more niche an information is the interesting it is. On the other hand, if the content is too specialized, in any case, the participants won't be able to follow.

Photograph 2: Dr. Oishi experimenting with hat making (June 2019, at the National Museum of Ethnology. Photography by Kayoko Saotome)

You have taken part in developing National Museum of Ethnology worksheets which visitors can complete when touring the museum on their own. What is different about the new worksheets?

We, the members of the earlier-mentioned working group have developed new Minpaku worksheets. We first reviewed the existing worksheets as well as survey reports of their users and the government’s curriculum guidelines for elementary schools. We then developed worksheets with two main objectives in mind: 1) to make them easier and more convenient to use and 2) to develop worksheets of a type new to Minpaku.

For the first objective, related to the worksheet’s physical form, we changed the size, material, and layout. They are now uniformly A4-sized, so that they fit easily into the A4-size binder the students carry during a tour to Minapku. We used paper that would make the sheets easier to write on. The layout, too, is designed to make them easier to go over. The previous worksheets varied in size and design; we unified the design for all the ten types of worksheets so as to facilitate filing and keeping them as a series. We also made the worksheets attractive so that visitors would want to come back and collect all the types of Minpaku worksheets.

The second objective had to do with content. The existing worksheets are of several types: task type, i.e., coloring pictures of museum materials, writing hieroglyphics; commentary type, i.e., searching for specific museum pieces in the galleries, observing them and reading their identification plates; and fill-in-the blank type, or observing exhibits and writing about the content and information learned for specific objects. These existing worksheets are interesting, it is true, but survey results so far show that, for the comment and fill-in-the-blank types, for example, worksheet users were likely to focus their attention so much on locating the specified museum materials in the vast gallery that they did not have time to carefully observe each material. Quite often the materials end up being no more than checkpoints quickly passed by. Another problem was that the museum materials to be observed were selected in advance and there are model answers for the fill-in-the-blank worksheets. While they were convenient for school teachers, they diverted student-visitors’ attention from other, non-designated items on display.

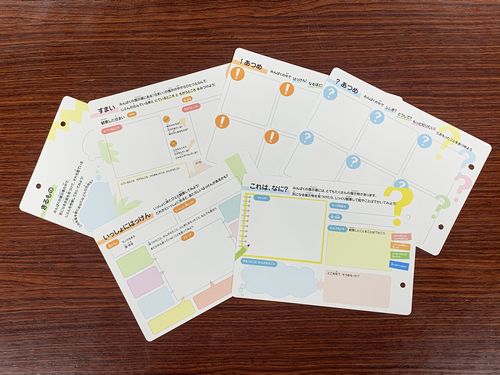

So, we decided to develop worksheets of a type that would allow users to pursue their own interests and observe and think about the materials they choose on their own. We visited the National Museum of Art, Osaka, a pioneer in producing worksheets of that type, to observe and learn about worksheet making (see photograph 3). We produced prototypes (see photograph 4) that provide far less information than before and no model answers, the worksheets were designed to encourage users to write in freely. Take, for example, the worksheet “What’s this?” You choose only one museum material you are curious about, observe it, and describe it in detail with sketches or in words. The sheet gives several points to keep in mind in observing things. What is intriguing about this worksheet is that you can write in what you think about the material and why. You can thus record what you feel and think after carefully and objectively observing things and drawing as much information from them as possible. By doing so, you can organize your way of observing items on display and your views about them, and utilize the worksheets for later study.

Photograph 3: Learning about worksheet making at the National Museum of Art, Osaka (March 2019. Photograph by Kayoko Saotome)

Critiques received at the phase of prototype development included comments such as that such sheets would be difficult for users not used to working on their own. With no model answers, teachers would find them difficult to use, and information would not be conveyed accurately. In my view, however, the worksheets have high versatility; they can be used in various ways depending on what is taught or learned before the visit or after it is over. Once these worksheets are made publicly available, I hope everyone will try them out.

Photograph 4: Prototype worksheets developed by Minpaku’s social outreach projects working group.

Do you have some advice for researchers who want to incorporate or embark on activities like those you have pursued as a liberal arts communicator? How should they proceed?

Based on what I have learned, including the bitter experiences mentioned above, let me offer three pieces of advice.

First, instead of choosing a topic outside your specialty or a topic pursued by other researchers, it may be best to focus on conveying something from the latest findings of your own research. That is sure to be easier to proceed with. In the case of the hat-making workshop mentioned earlier, since I had never done research on hats before, I faced great burdens of background study and preparations. I suggest you choose a research topic that not only won't demand too much from you but will also boost your motivation to do outreach activities.

Second, it is wise to specifically define your audience—the people to whom you plan to convey your research findings or with whom you want to engage in liberal arts communication. In doing so, it will be easier to identify the effective means of communication. Last academic year I was involved in developing a board game The Arctic, part of Japan’s national project Arctic Challenge for Sustainability (ArCS, 2015–2020). In any field of research, it is quite common to organize symposiums and lecture meetings for the general public as part of outreach activities. The majority of the participants of such events are the elderly. To encourage more junior and senior high school and college students—future scholars and the young people who are the pillar of our society—to attend, we came up with the board game, which young people can enjoy playing and which helps them learn about the current status, anticipated future changes, and the resulting issues in the Arctic.

Third and lastly, acquaintance with researchers in other fields, artists, private-sector company employees, and so forth is invaluable. In disseminating your research results to the general public, collaboration with people in other fields can bring about new channels of communication with specialists who had little previous interest in your field. Fresh dialogue with them may lead to new research possibilities. By talking with people in other fields and through collaborative projects with them, you will develop means of communication that would be impossible if you were confined to your own research field and techniques. The possibilities for collaborative research with other fields will expand significantly.

(Interview: Ayumi Koso)

Liberal arts communicator, National Institutes for the Humanities Center for Information and Public Relations; Project assistant professor, National Museum of Ethnology

Oishi received her PhD in Social Anthropology from the Graduate School of Humanities, Tokyo Metropolitan University in 2018. She was a postdoctoral fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science at the Center for Northeast Asian Studies, Tohoku University before assuming her current position. Oishi’s research interests are environmental changes in the Arctic and human society, subsistence complex in Siberia, and the culture of furs.